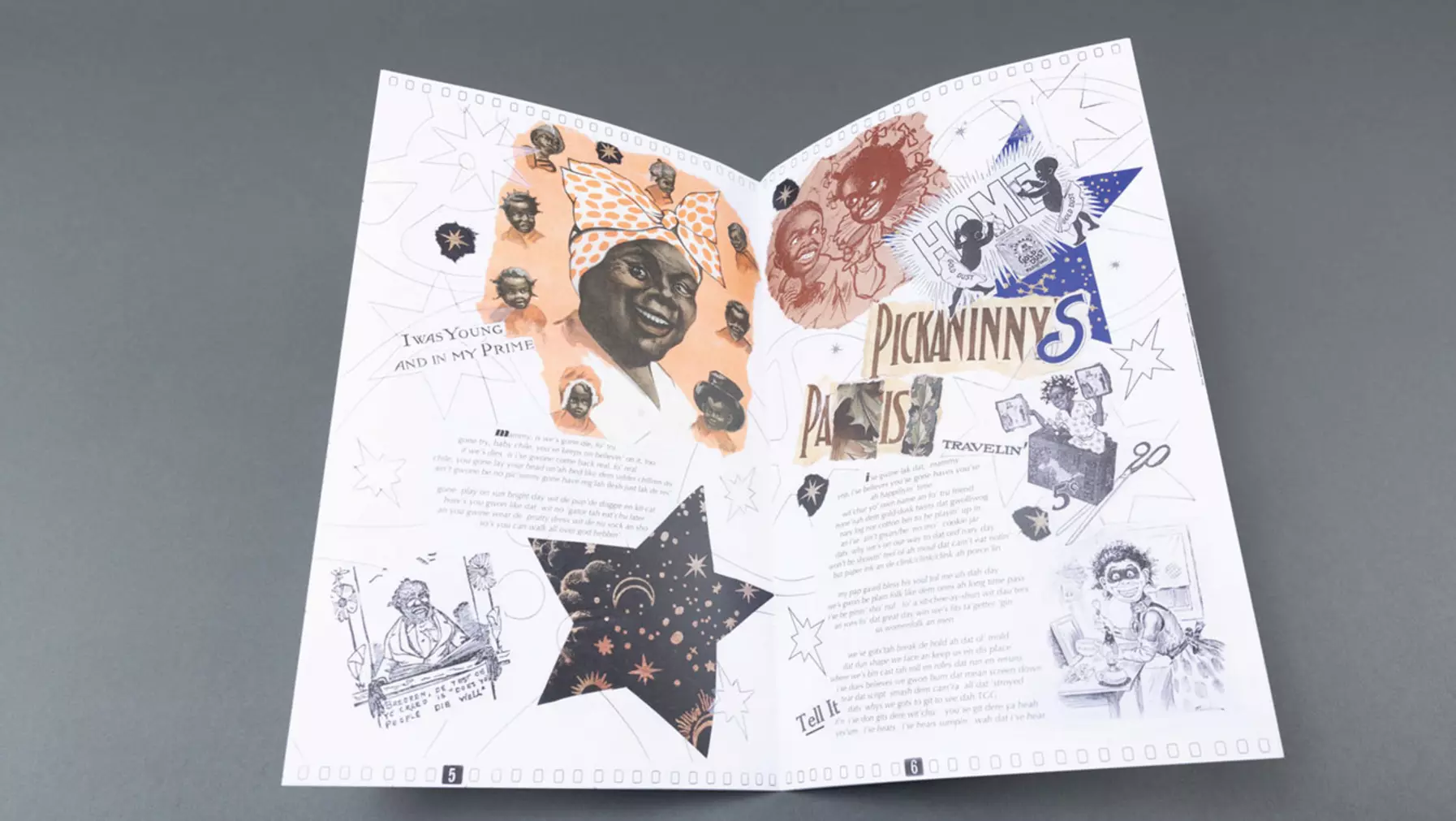

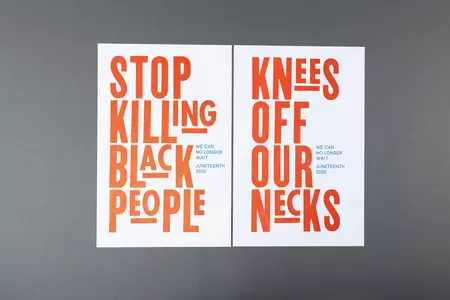

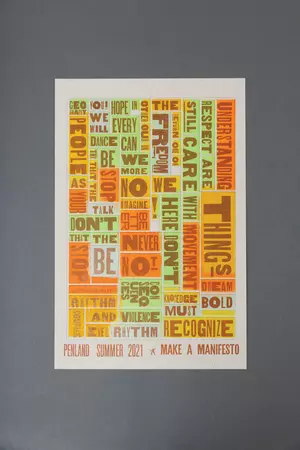

An exhibition at Collins Memorial Library highlights how artists’ books can challenge beliefs and ideas—even the very idea of what a book is.

Is a book a book if it has no words? Must a book’s content be constrained within its cover? While the vast majority of Collins Memorial Library’s holdings meet the traditional definition of a book, a new exhibition in the library introduces visitors to a category of works—artists’ books—that challenges not only the very concept of a book but many long-held beliefs and ideas facing our society.

Changing the Conversation: Artists’ Books, Zines, and Broadsides From the Collins Memorial Library Collection, which runs through Dec. 16, showcases examples of this highly creative medium of artistic expression, which uses the structure or form of a book as inspiration. The exhibition is the brainchild of library director Jane Carlin, who has a deep knowledge of, and affection for, artists’ books.

For 20 years, Carlin was head of the Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning Library at University of Cincinnati. Upon joining University of Puget Sound in 2008, she started acquiring artists’ books for the library’s special collections division and also helped form the Puget Sound Book Artists organization, which now has more than 100 members. Each summer, the library hosts the organization’s annual member exhibition. Changing the Conversation is the first exhibition that showcases only the library’s own collection of artists’ books.

“Our goal,” Carlin says, “is to demonstrate how these publications can help change the conversation by promoting discussion about difficult issues and by learning from personal narratives and stories of the artists who created them.” The exhibition features a range of voices that together form a compelling chorus on issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion.