In his newest book, historian Adam Sowards ’95 examines the long-running tensions between environmentalists and industry over public lands in the West.

While growing up near Seattle, Adam Sowards ’95 wasn’t exactly a lover of the outdoors. In fact, when he enrolled in an environmental history course during his junior year at Puget Sound, he was driven more by the insistence of his advisor, Bill Breitenbach, that he diversify his coursework as a history major than by the prospect of actually learning about the subject. And then, in about week three, inspiration struck. “All of a sudden,” Sowards says, “all the history I thought I knew looked different when I looked at it from this different angle.”

That course, taught by former Puget Sound professor Andrew Isenberg (now at the University of Kansas), combined with another course Isenberg taught about the history of the American West—as well as classes taught by Nancy Bristow—didn’t just wake Sowards up to new possibilities. They inspired his entire career.

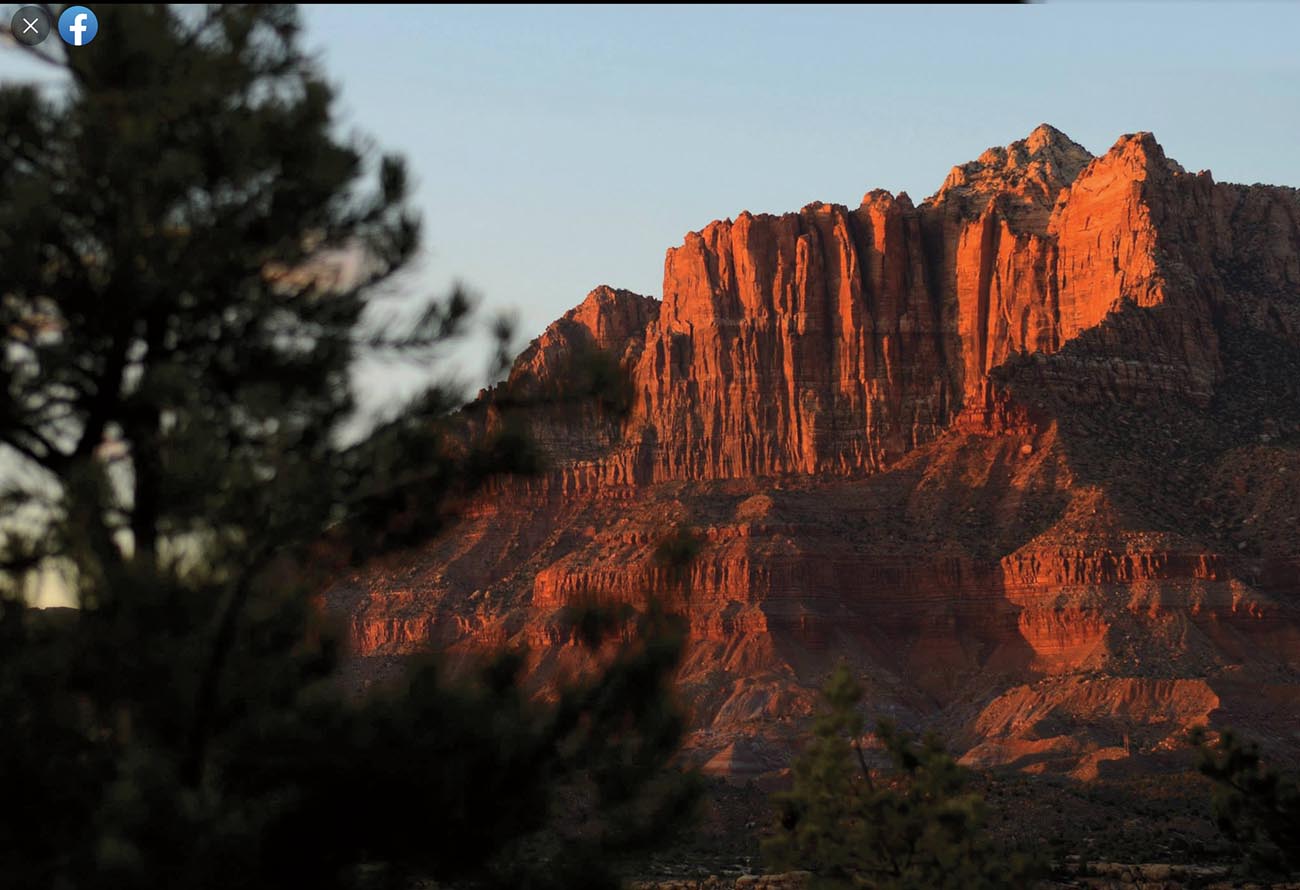

With his focus on the intersection of the history of the American West and the history of the environment, Sowards, now 49, went on to Arizona State for graduate school. Until recently, when his wife took a new job in Western Washington, Sowards was a history professor at University of Idaho. And in April 2022 alone, he saw the publication of both a brand-new book—Making America’s Public Lands: The Contested History of Conservation on Federal Lands—and the publication in paperback of his previous book, An Open Pit Visible From the Moon: The Wilderness Act and the Fight To Protect Miners Ridge and the Public Interest, which won the Hal K. Rothman prize from the Western History Association.