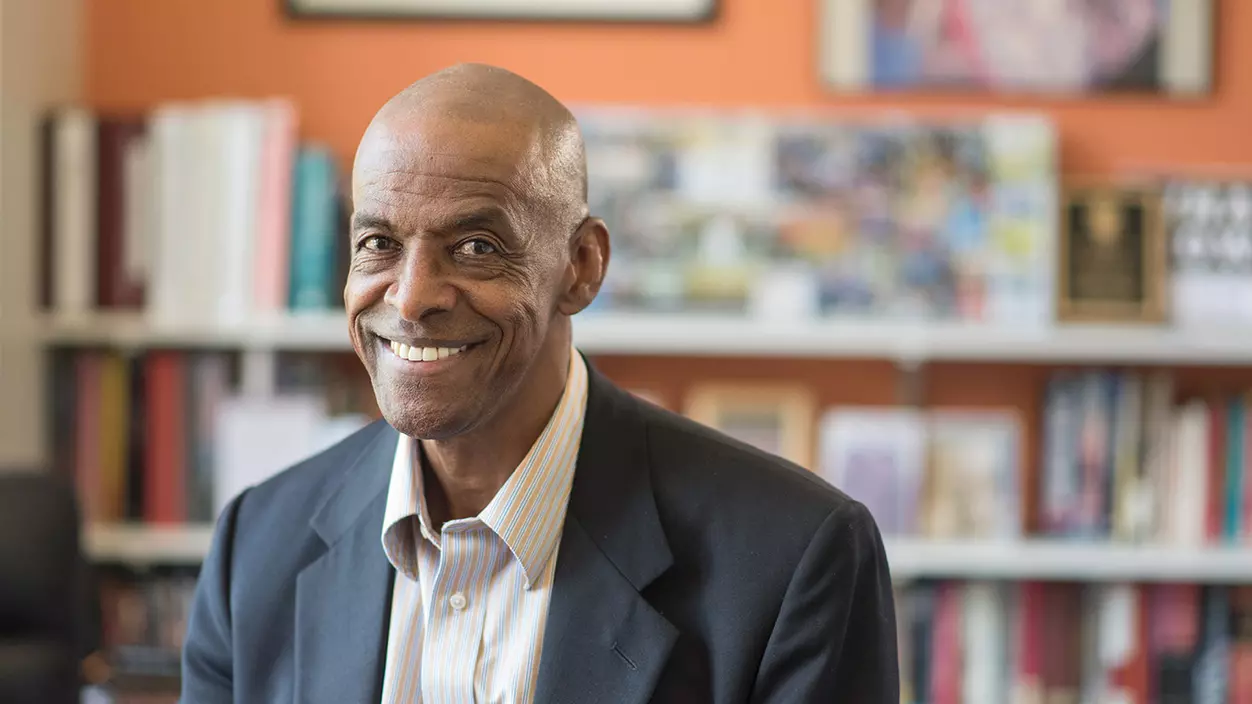

Q: What prompted you to leave Jamaica to pursue further degrees?

A: In 1979, I went to the Bahamas as a youth community organizer, and I was invited to address a gathering on Rastafarianism. A TV station turned up, and their immediate question was, “What qualifies you to speak on this? What degrees do you have?” At that time, I hadn’t gone to college. I was so mad, and I said, “I grew up with Rastafarians. I know this culture. I know Rastafarian philosophy thinking.” The television station crew left because it was not worth covering this event. I swore there and then that nobody would ever lock me out of an opportunity because of a lack of certification.

Q: You were offered a job at Puget Sound while you were teaching at the University of Alabama. What were your first impressions?

A: I was attracted to this region because it met an immediate felt need for me. I looked around and thought, “This is it. This is the place.” Because as a child, I grew up watching the sky meet the sea, that horizon of expansive possibilities. That was my canvas for my imagination. I was always thinking, “What is beyond those horizons?” After that, I thought how small the place was. And then, the racial makeup of the place, the dominance of white students, white faculty, white staff. By then, I had something of a clear sense of my mission.

Q: Your mission?

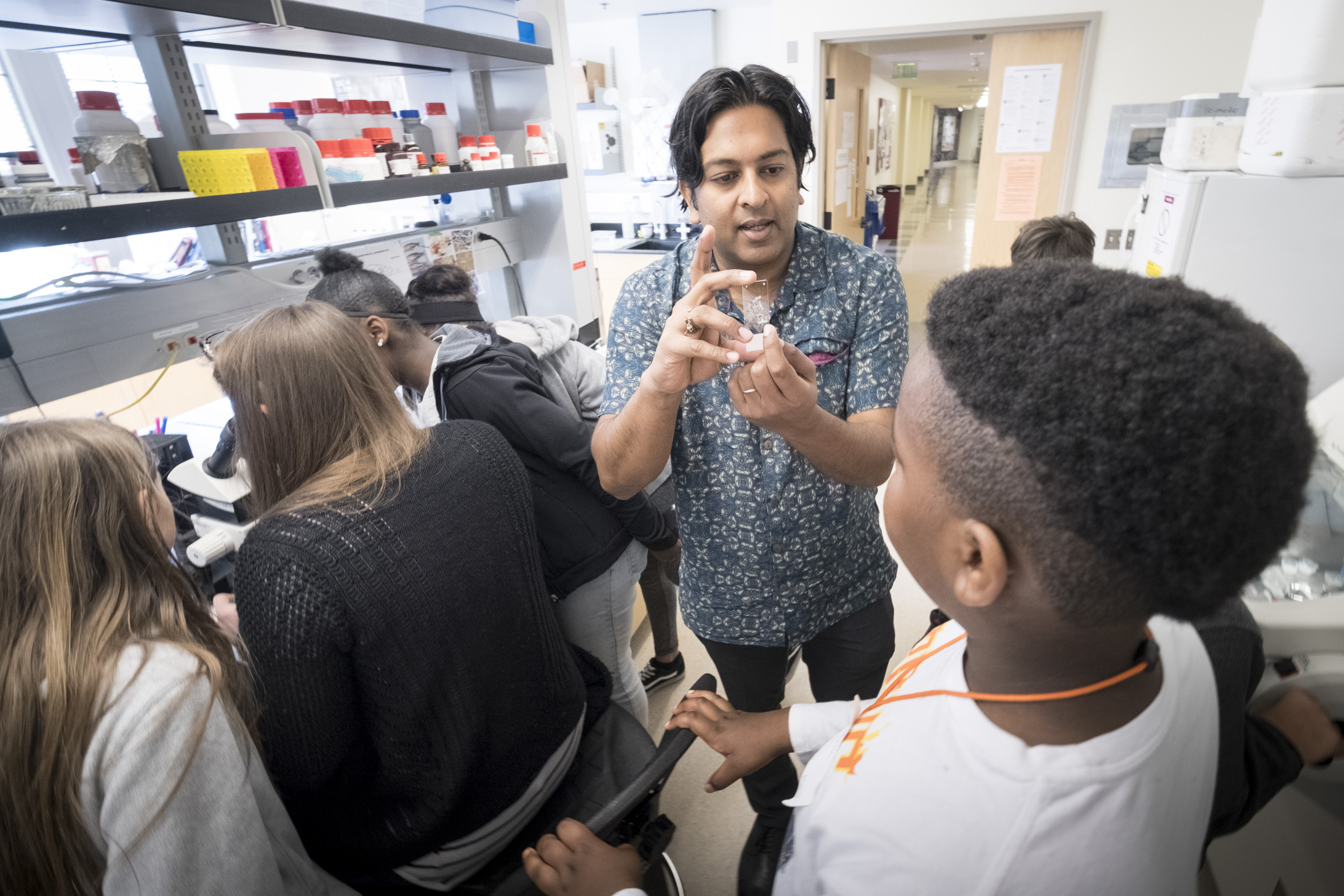

A: Yeah. In Jamaica I was very active in Youth for Christ. One of the things I noticed, working on the streets of Kingston, was that the local colleges had no connections with their local communities. I said, I want to go get a Ph.D., because I want to connect the work of universities with the lives of people in communities. When I came here, I went to the Black Collective [Tacoma community group]. I said to them, “If you promise to connect me with black communities, my commitment is to connect the university with those communities.” That’s the work.

Q: How did the Race & Pedagogy National Conference come about?

A: I began to think about “How do we get this university to think about the issues related to black life?” Then, there was this black-face incident with a white hip-hop group. [Later] there was another black-face incident. That led me to write an open letter to the campus, because the students who were at the heart of this had stock answers: One, we meant no harm; two, we did not know any better; and three, [the African American students who objected] are overreacting. I pointed out the irony that we are an institution that is supposed to focus on knowledge production, knowledge dissemination. Yet, the main justification for this course of action was ignorance.

Q: And you had supporters who also felt something must be done?

A: A whole group, including [Professor Emerita] Juli McGruder, organized teaching sessions for campus. Later, I sent an email to faculty inviting them to a brown-bag discussion with a single question: What’s the role of race in the development and delivery of your curriculum? We gathered for that first brown-bag session, and for two years, we had four per semester. In 2004, we proposed to host a conference. For the first one, in 2006, we had over 2,000 people participate. That was the beginning of the Race & Pedagogy Institute.

Q: What is the Race & Pedagogy Institute’s most noteworthy accomplishment?

A: Repositioning race as a legitimate, viable intellectual project, as against the usual shouting matches we have or the usual polemical argument we have about race. I’m not suggesting that we were the first or the only ones, but anywhere in this region now you can talk about race [in schools].

Q: Of course, talking about race also leads to discussions about other marginalized people and their causes, such as protesters at Standing Rock and DACA recipients. Where does intersectionality come in?

A: It’s an important point. We work, but not necessarily for cohesion. We are interested in collaboration. I want to recognize the right of every other group to exist and to work to advance their own causes. I want to support them in these efforts. The work is always going to be noisy and messy and hard. But if we maintain our common commitment to justice, I think we will advance this cause.

Q: Are you optimistic change will come more quickly?

A: I would say I am hopeful. I have to have hope, because the alternatives are not acceptable.

Q: This is heavy work, with the risk of backsliding. How do you relax?

A: I love playing soccer. As long as these knees will carry me, I will play soccer. I love being with family. I’m a product of my family and my community. I do my work on their behalf.

For more information and to register for the 2018 Race & Pedagogy National Conference, happening Sept. 27–29, go to pugetsound.edu/rpi.