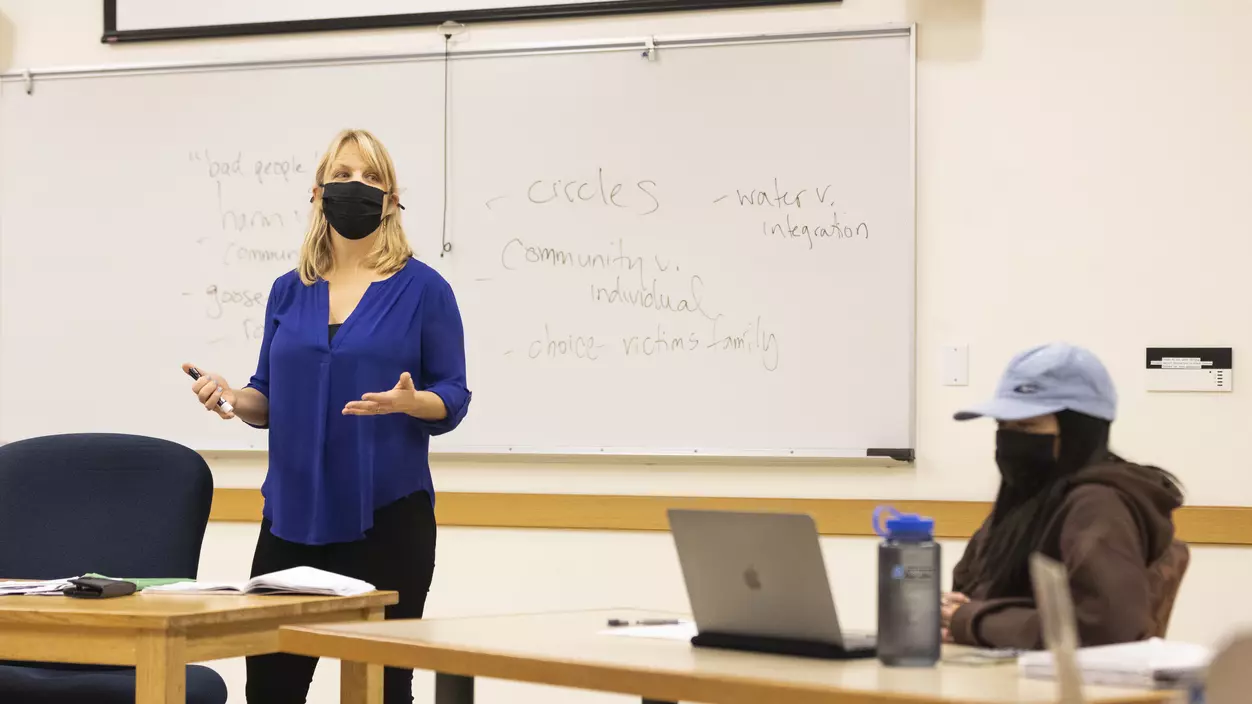

Tanya Erzen is visiting associate professor of religion, spirituality, and society and director of the Crime, Law, and Justice Studies Program at University of Puget Sound

When Tanya Erzen is not in a university classroom, she can be found in prison. As a co-founder of Freedom Education Project Puget Sound (FEPPS), Erzen teaches college courses to people serving sentences at the Washington Corrections Center for Women. Since FEPPS’ accreditation in 2014, more than 250 women have taken classes and 35 have earned associate degrees. Currently, there are 15 students enrolled in a bachelor’s degree program through the University of Puget Sound. FEPPS is one of Erzen’s many passion projects—all aimed at prison reform and transformative justice. Her latest project is a program in crime, law, and justice studies at Puget Sound now offering classes to students registering for spring semester. We sat down with her to talk about this new program, her interest in prison reform, and her life outside of work.