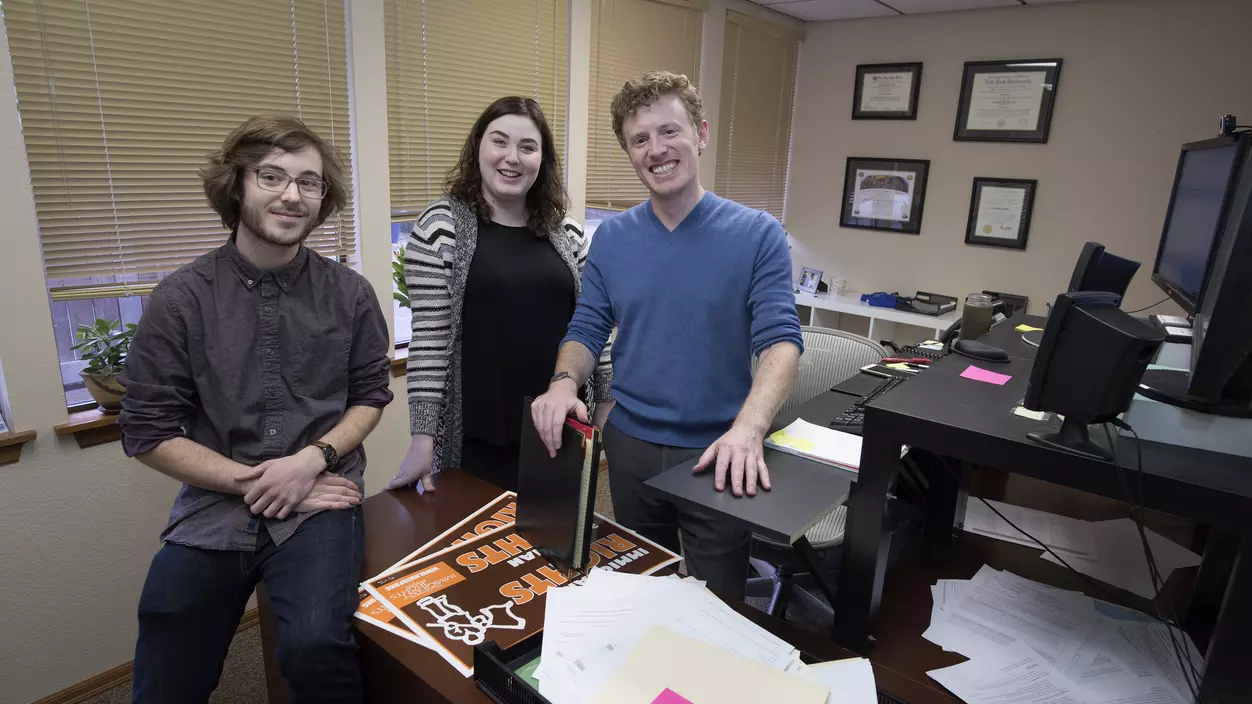

Evan Eurs ’18 put compassion into action as an intern with the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project.

Many Tacoma residents may not be aware that one of the country’s largest immigration detention centers is in their city. Evan Eurs ’18 certainly wasn’t before he began an internship with the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project (NWIRP), in partnership with Puget Sound’s Summer Immersion Internship Program.

In fact, Evan, a Hispanic studies and mathematics major, knew very little about immigration, other than what he saw in the media. Working on cases for people held at the Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) gave him a new perspective. “People in detention don’t fit the stereotypes of undocumented immigrants,” he says. “The internship humanized detainees for me.”

With a skateboard under his arm and a baseball cap turned backwards on his head, Evan looks younger than he sounds as he enthuses about his summer working at NWIRP. He was “blown away” by having access to the detention center and being allowed to work one-on-one with clients. “It felt so above my role as an intern, but [NWIRP] had faith in me, they wanted the help, and they were like, ‘Yeah, you can do it.’”

He’d been surprised to learn that people in immigration court do not have the right to an attorney, an issue at the heart of NWIRP’s work. The organization began in Seattle with a single staff person recruiting volunteer attorneys to represent people fleeing civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala in the 1980s. It has grown into one of the largest organizations in the country to provide legal assistance for immigrants, with more than 80 staff members in four offices, including two in Eastern Washington.