Participants in a Community Summer class see the history of the Native American experience through the eyes of an Indigenous instructor.

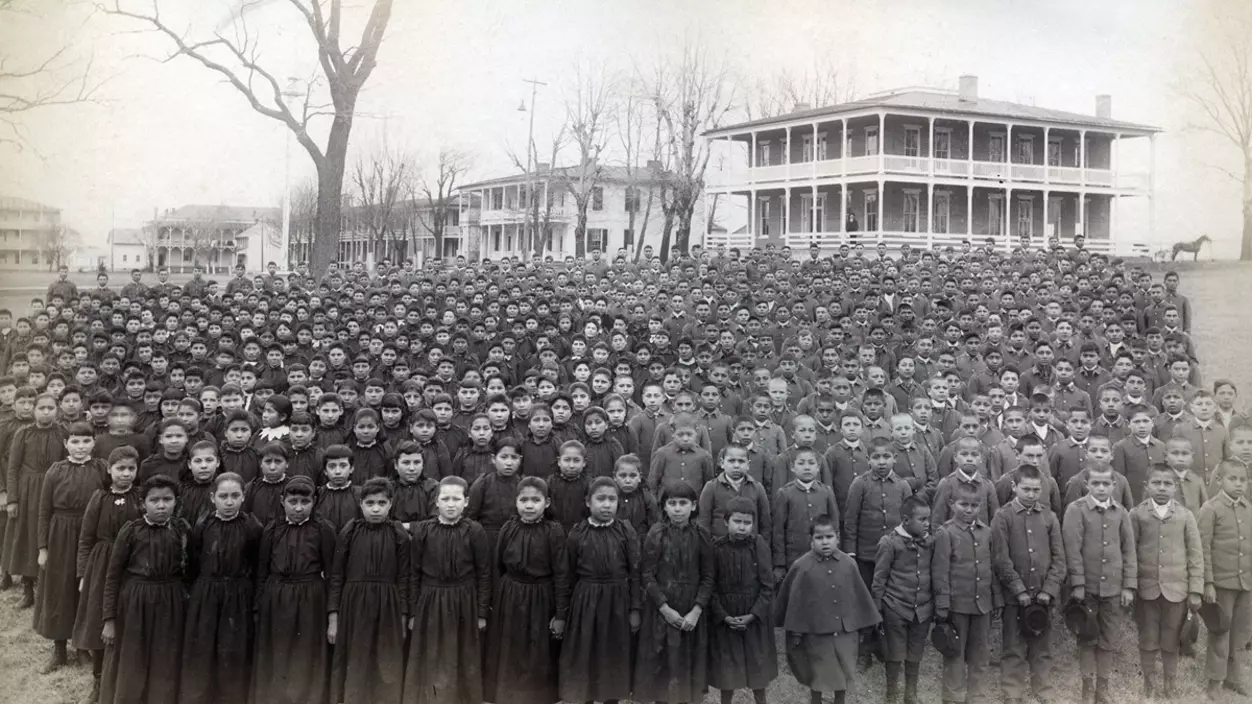

Over the summer, 30 people—some from campus, many from the local community—spent a series of Saturday mornings in Howarth Hall hearing about a weighty subject: the history of Native Americans in the U.S.

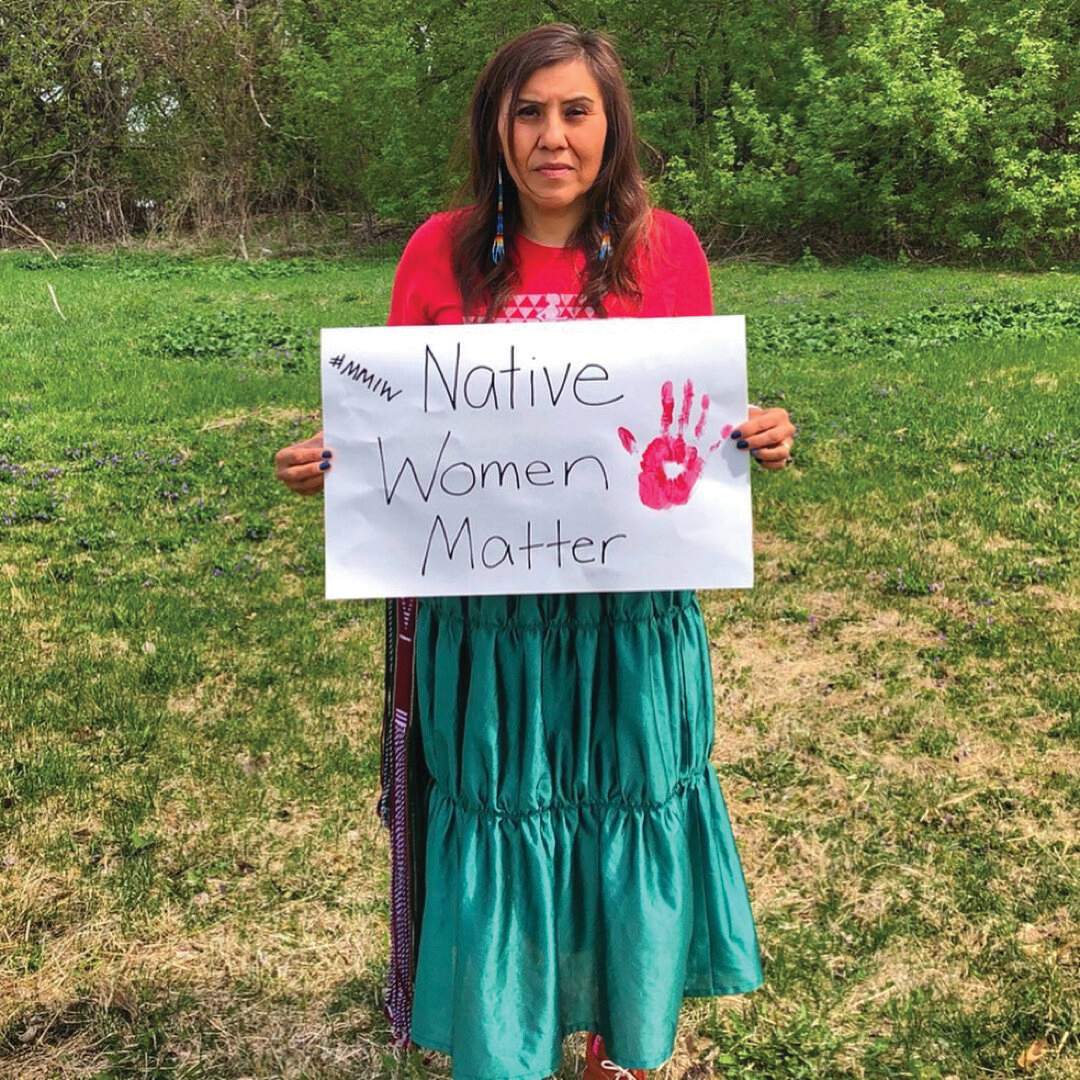

Instructor Doris Tinsley, a member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation, billed the class as a “crash course,” and it lived up to its name, covering more than 500 years’ worth of American Indian history in just a handful of sessions. Tinsley touched on everything from the arrival of the Europeans in the late 15th century to the modern-day crisis known as MMIW, for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women.

“Crash Course Intro to Native American Studies and Contemporary Issues” was one of 16 classes the university offered in the Community Summer program, in which faculty and staff teach non-credit courses open to the public. This summer’s topics included music production, yoga, ceramics, the history of cancer, and even a bit of quantum mechanics.

Many who signed up for Tinsley’s course cited her heritage as a plus. “The advantage for me was that Doris is an Indigenous person herself. Such resources are very hard to come by,” says Douglas Cannon, a Puget Sound emeritus professor of philosophy who has long been interested in Native American issues. “Her perspective was different from what I had ever been exposed to in a classroom.”