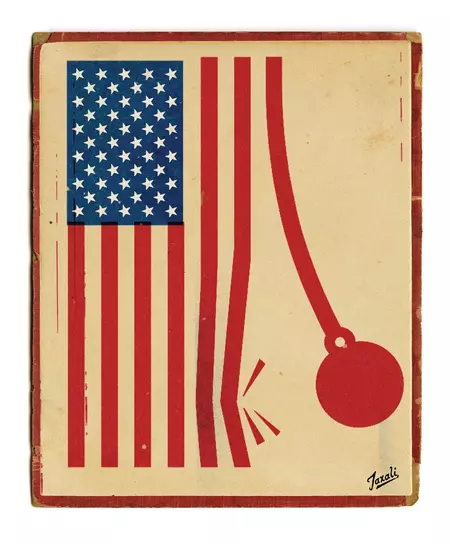

What motivates people to take up arms and kill for a political cause? In part, it’s a belief that their future is uncertain, and that “others” are the cause of that uncertainty. In a multiethnic liberal democracy like ours, that fear can set in when the majority begins to lose control. And in the 2020 U.S. census, for the first time, the white population declined in absolute numbers. The far right refers to this as “White genocide” or “Great Replacement”— not that people are actually killing white people, but that white people will no longer be the majority, and will lose the ability to control their own political future.

The problem is that the ideology of the extreme far right—this concern over eroding white power—is being adopted by more mainstream Republicans. Extremists’ views and misinformation on a range of issues—the 2020 presidential election, COVID-19, the 1619 Project, critical race theory, and more— are feeding into a larger narrative that liberal democracy and protecting the rights of people who don’t look like you are not good for you, that others threaten you, and that democracy itself is dangerous. And that’s the threat—it’s not just that of political violence, but the dismantling of liberal democracy.

Politics is really hard; it’s about compromising with people who have different interests than you.

In The Republic, Plato confronted the issue of how to get people to love their political community as well as the others who live in it and put its needs before their narrow and selfish interests. He argued that a “noble lie” was needed to bind people together. America has such noble lies—think about the metaphor of the melting pot, the myth of the first Thanksgiving, or even the notion of the American dream. All of these stories serve to make us love our country and those in it, even as we recognize that all of these stories are, to some degree, lies.

Abraham Lincoln confronted this very same problem—how to hold together a country when one side saw the other as threatening its very existence—during the Civil War. His solution: to adopt the Declaration of Independence as our “political religion.” Lincoln recognized that while the promises of the declaration were a lie to many, aspiring to fulfill those promises could serve as a noble lie that “links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together.”

How do we live with people who are unlike ourselves and who hold beliefs different from ours? How do we craft a future that allows everyone to flourish in ways that don’t depend on the denigration or oppression of others? This is a problem that, I believe, a liberal arts education is particularly well suited to address. A liberal arts education exposes us not just to diverse ideas but to diverse people, both of which challenge our own understandings of truth. It must also teach us how to live together with people who are unlike ourselves; that is the highest test of democratic citizenship.

The best starting point is to dedicate ourselves and our students to the task before us: the defense of the American experiment in democracy. That means upholding the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and aspiring to spread those ideals to those who currently do not enjoy them. It means acknowledging when, where, and why we have failed to live up to those ideals. And it means embracing the proposition that all people are created equal and that, regardless of the differences in our identities or beliefs, nothing we do should move us away from that ideal, only closer to it.