Nabil Ayers ’93 describes his new book as “a memoir about one man’s journey to connect with his musician father, ultimately re-drawing the lines that define family and race.” In this excerpt, Ayers recalls some of his experiences as a Puget Sound student.

Nirvana’s debut album Bleach was released in June 1989. Three months later, during my first week of college, Soundgarden released their second album, Louder Than Love. And that November, Mudhoney’s self-titled debut arrived. “Grunge,” I quickly learned, was a real thing, and bands from Seattle were playing powerful, heavy, sweaty music at exceptionally high volumes and rebelliously slow speeds.

I’d chosen a college in the Northwest for a few reasons: I wanted to leave Salt Lake for a bigger city; I didn’t like California, which felt fun to visit but too one-dimensional to call home; and I wanted to be closer to music. Seattle simply felt musical, with record stores and venues everywhere.

At UPS, I barely hung on academically. But I excelled in other ways. Tons of kids at UPS played music, and it was easy to connect with them in the close quarters of my freshman dorm. Both of my roommates were musicians. Jon was a tall, quiet academic from nearby Kent, Wash., who played trombone. Luke was an energetic pre-med student who had grown up in Eureka, Calif., where he played trumpet in Mr. Bungle, the band Mike Patton left (and eventually returned to) to join Faith No More just before they recorded their breakthrough album The Real Thing.

I shared a weekly radio show with my friend Jason Livermore ’93, a handsome jock who was on a swimming scholarship. Jason was a drummer who’d lived outside of Berkeley, Calif., and had seen punk shows at the legendary venue 924 Gilman Street. We knew that nobody listened to our show on KUPS, but we used our two-hour shift to rapaciously explore the station’s music library and educate ourselves. We read the weekly trade magazine College Music Journal cover to cover, and other times, we simply pulled CDs off the shelf and played them because they had a cool cover, or because they had Sub Pop or Matador or 4AD logos printed on the spine.

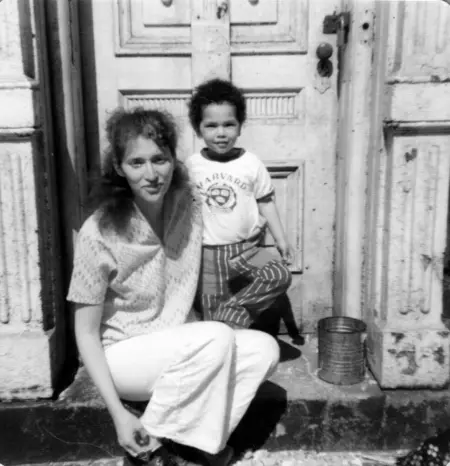

Forty percent of UPS students were fraternity or sorority members. My childhood photos weren’t of me on boats or ski slopes, they were of a half-Black, half-white, hippie kid with an afro, wearing raggedy clothes and holding a pair of drumsticks on an urban sidewalk—a very happy kid, but one who didn’t fit the fraternity mold. But I was curious enough to give the fraternity system the benefit of the doubt.

My freshman friends and I went through rush, the very organized process in which prospective fraternity members visit each house and meet its members. Over the course of four days, each rushee spends an increasing amount of time at a decreasing number of houses, based on a mutual ranking system. I’d met a lot of people whom I really liked—people from Salt Lake, people who liked the same bands I did and had other shared interests. And they seemed to like me. Nobody asked the questions I feared: What does your father do? What kind of car do you drive? What race are you?

Still, I wasn’t entirely comfortable. There’s a scene in the movie Animal House in which some nonwhite men are rushing. They’re treated well on the surface— greeted with smiles and firm handshakes, but then they’re pawned off on the least desirable members of the fraternity. Was I that guy? It was the members’ job to make everyone feel welcome, but was I truly welcome? I feared that my race and socioeconomic background made me a prime candidate to be, at best, uninvited to join a fraternity or, at worst, humiliated during the process of trying.

On the final day of rush, I was asked back by my top two fraternity choices. But my second choice scared me. The guys were tightly wound and had stereotypical fraternity nicknames like Puddles and Chainsaw. The blond, buttoned-up, chisel-jawed house president could never pronounce my name correctly. Happily, I accepted an offer from my first choice along with two dozen other freshmen.

Should I be in this fraternity? I sometimes thought after I joined. Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity was founded in 1856 in Tuscaloosa, Ala. All eight of its founding fathers fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. But more often, I thought it was important to be there, among a relatively mixed group of people—some of whom were Jewish, Hispanic, Indian, Black, Japanese, and gay—helping the system to evolve, rather than rejecting it based on its history.

I’d been close with the same college buddies for two years, so in retrospect, I’m not sure why it took Jason and me so long to start a band. We had always made a point to see music together. In 1991, we walked two hours in the rain from our parking spot to see a show on the first Lollapalooza tour, with Jane’s Addiction, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Violent Femmes, Fishbone, and Ice-T and Body Count. We drove two hours south to Portland instead of to nearby Seattle in order to see Sonic Youth in a smaller, better venue. We sweated in a cramped Seattle record store while Nirvana debuted songs from their not-yet-released album Nevermind for a lucky roomful of fans.

In our junior year of college, we finally got our act together and started our band. I played guitar, Jason played drums, my freshman roommate Luke sang and played trumpet and keyboards, and our bespectacled, lacrosse- playing friend Chris played bass. We covered college-friendly party songs by Jane’s Addiction, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Alice in Chains. And finally, we started writing our own music. It wasn’t easy.

At night, Jason and I continued to see bands—loud, straight-ahead bands like Seaweed and Mudhoney, but we couldn’t write music like theirs. On our radio show, we continued to play lazy guitar bands like Sebadoh and Pavement, but we couldn’t write music like theirs either. Everyone in our band was technically a good musician, which I later realized might have been a handicap: Some of the best bands are great because, while they might not be masters of their instruments, they have something to say. Music is a powerful vessel for a message, especially when its looseness fosters an emotional connection. We, unfortunately, were very tight, and while it was a ton of fun, there was no real passion in what we did.

After a few shows, it became time to name our band. Spontaneous Funk Whorehouse quickly stuck, and although it stands out as one of the worst band names I’ve ever heard, it did kind of fit our sound, a college band that couldn’t decide its focus. Our music leaned toward off-kilter, percussive Bay Area bands like Mr. Bungle and Primus. Our friends called us SFW for short, and those who didn’t like us called us So Fucking What. We quickly advanced from college house parties to local Tacoma bars like Magoo’s and Cheers West.

Within a few months, we recorded a five-song demo, which took two full days and served as my first time recording in a real studio. I loved the smell of new carpet and the fact that we spent more time meticulously tweaking sounds and mixing the tracks than actually playing. We had an engineer who gave us positive reinforcement but also told us when we should change a part. In the studio, we were a real band. SFW pressed 100 cassettes and they sold out right away. Soon, SFW released a CD. We received heavy airplay on the local radio station KGRG, which had a strong signal and real listeners.

I’ll never forget the first time I heard myself on the radio and cranked the volume in my friend’s car as we turned a corner onto campus. Even though I knew KGRG was a small station, I was famous for those three minutes.

In my junior year, I’d been elected social chairman of my fraternity, where I did more than simply plan parties. I handled weekly negotiations with the dean’s office to get our alcohol permits signed before parties. I oversaw a healthy budget. I instituted a system of creative accounting so that sororities could contribute to alcohol purchases for the first time ever—something they were strictly forbidden to do. I hired live bands and brought in fencing companies so we could expand our parties outdoors in the spring. And I listened to and represented 100 people, many of whom didn’t always agree on our party strategy. It was my first real job, and I poured myself into my position, leading to my becoming president my senior year.

The president carried a big title—Eminent Archon. The title always brought me back to thoughts about the fraternity’s early days—it felt all too close to the KKK, who used titles like Grand Dragon and Grand Wizard to describe its leadership. But the thought of me, a Black, white, Baha’i, Jewish son of a single mother becoming Eminent Archon of a respected chapter of the biggest national fraternity ... I loved it. Not only had I joined the system, I’d beat it. My goal hadn’t been to dismantle it, but to continue to push it forward.

At UPS, I created a new student government position, overseeing the new Campus Music Network. There were several bands on campus, and I was given a budget to put on concerts, send each band into a proper recording studio, and release a compilation tape of the recordings. I was thrilled to hear that after I graduated, the program continued to exist and that each year a new compilation had been released on CD. My academic advisor, though disappointed with my poor academic performance for nearly four years, sat me down one day to tell me how impressed he was with the Campus Music Network and that he was submitting me for an award. I explained to him—unapologetically—that contrary to what my transcripts said, I was receiving an excellent education at Puget Sound. I may have majored in communication, but my real classes were deejaying at KUPS, playing in a band, interning at a record company, planning parties, and now overseeing the Campus Music Network.

That spring, I sat in a roomful of over-achieving seniors who I assumed looked down on me on the days that I did attend class, and I accepted one of the university’s highest honors, the Oxholm Award for Superior Service to the University Community.

From MY LIFE IN THE SUNSHINE by Nabil Ayers, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Nabil Ayers.