Kevin Covarrubias ’23 combined an internship with his summer research project to reduce pitching injuries

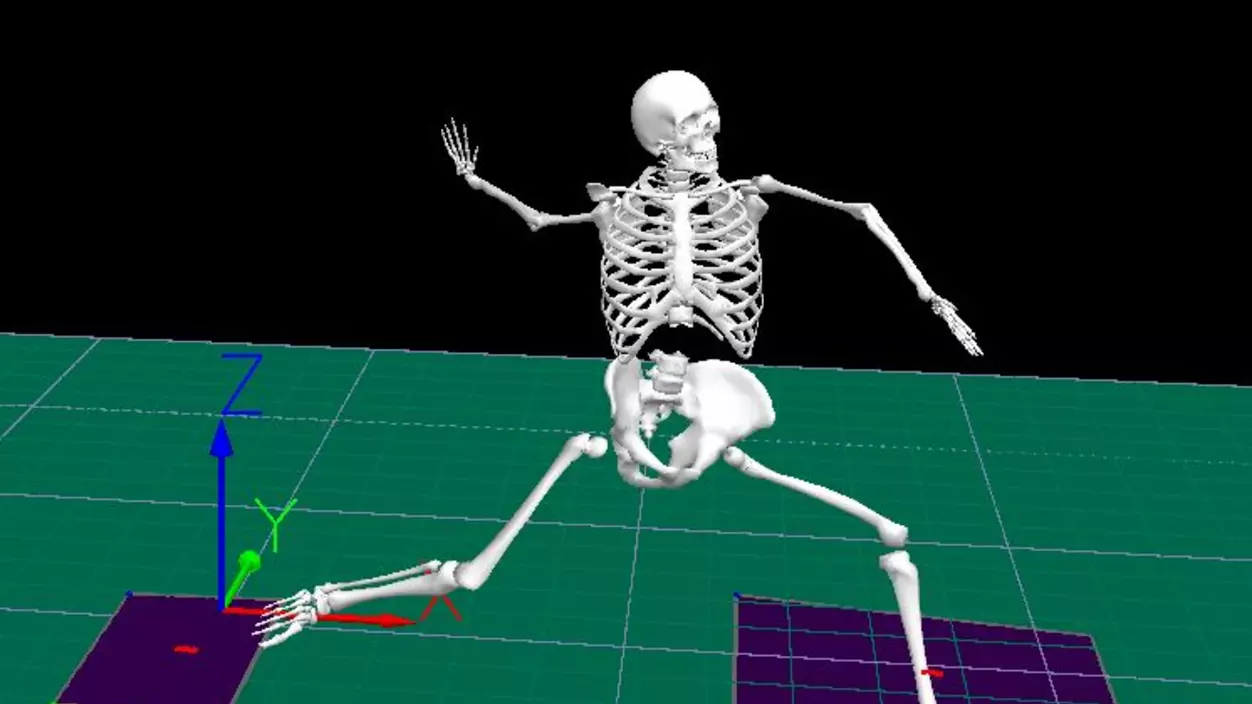

It’s midmorning at Driveline Baseball, a performance training facility in Kent, Wash., and Kevin Covarrubias ’23 is spraying a thin layer of adhesive on the skin of an athlete in preparation for attaching 45 reflective markers to their arms, legs, chest, and back. Once the markers are in place, he has them step into the center of a massive, motion-capture camera rig that will record their tiniest movements, track the movement of each marker, and send the data to a computer for analysis. It’s all part of the company’s data-driven approach to helping baseball players perfect their form. For Covarrubias, who’s interning at Driveline, it’s also the basis for his summer research project.

“I’m studying the biomechanics of pitching and, specifically, looking at torso and pelvis rotational kinetic energy and how that’s related to the speed at which they’re throwing,” Covarrubias says. “I played baseball in high school, so I know how easy it is to get injured. I’m hoping that my research can help players improve their throwing and understand how they can avoid hurting themselves.”