When it comes to health and health care, people of color are at a decided disadvantage. We asked some Logger experts what can be done.

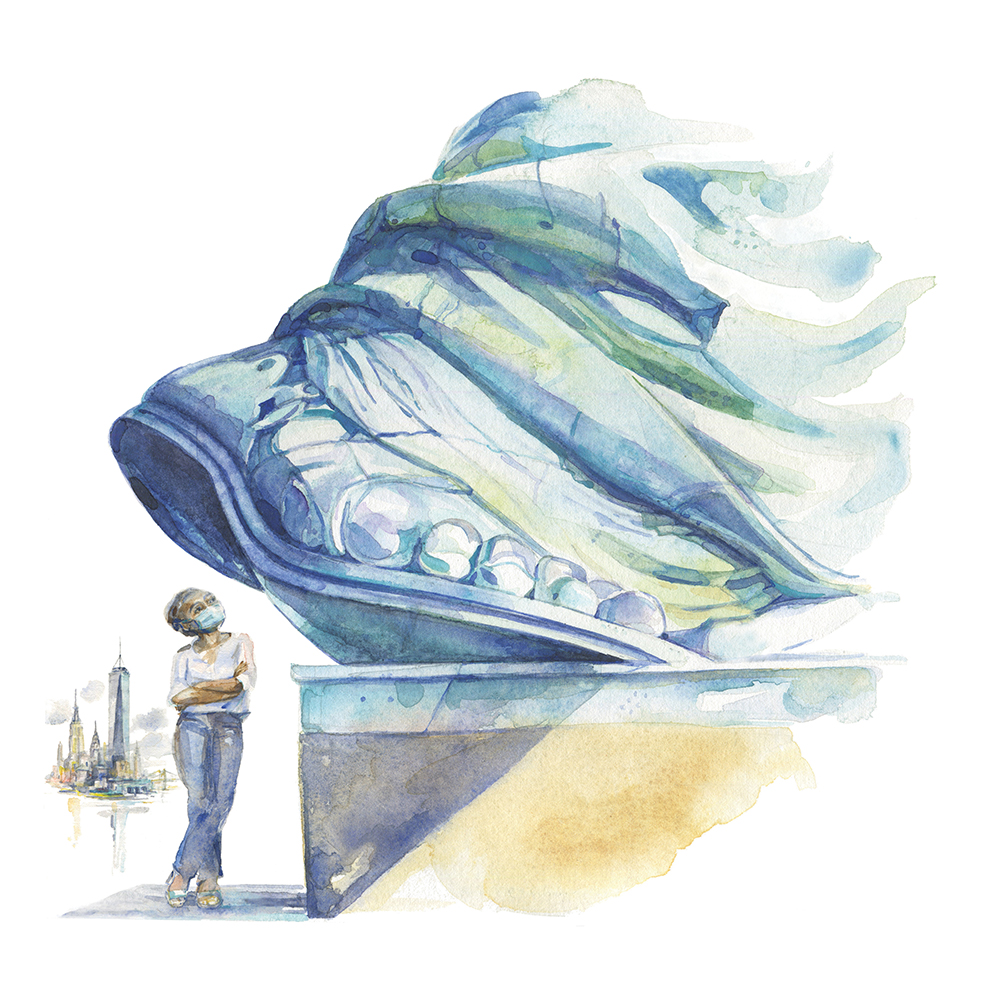

Preparing for a new baby during COVID-19 was not what Jamilia Sherls-Jones ’05 had hoped for. She wanted to touch the soft cotton of newborn onesies, turn over car seats to choose just the right one, judge—in person—which stroller, crib, and changing table were best. Instead, she was forced to do most of her baby shopping online. Many of her prenatal appointments went online, too.

But the inconveniences of COVID-19 were not the only pregnancy challenges confronting Sherls-Jones. During the weeks before the baby’s arrival, as Sherls-Jones and her husband organized the house and her mother prepared the baby’s room, decorating it in pinks, greys, and lavenders, with a rabbit theme, a disturbing fact hung in her mind: Black women in the U.S. suffer pregnancy- and childbirth-related deaths at alarming rates—three to four times more often than white women. Even being more highly educated isn’t enough to protect Black mothers in this country: A college-educated Black woman is at 60% higher risk of maternal death than a white woman with just a high school diploma. Sherls-Jones knew that being informed wasn’t enough to protect her—the knowledge, she says, “doesn’t necessarily make me immune from being a statistic.”