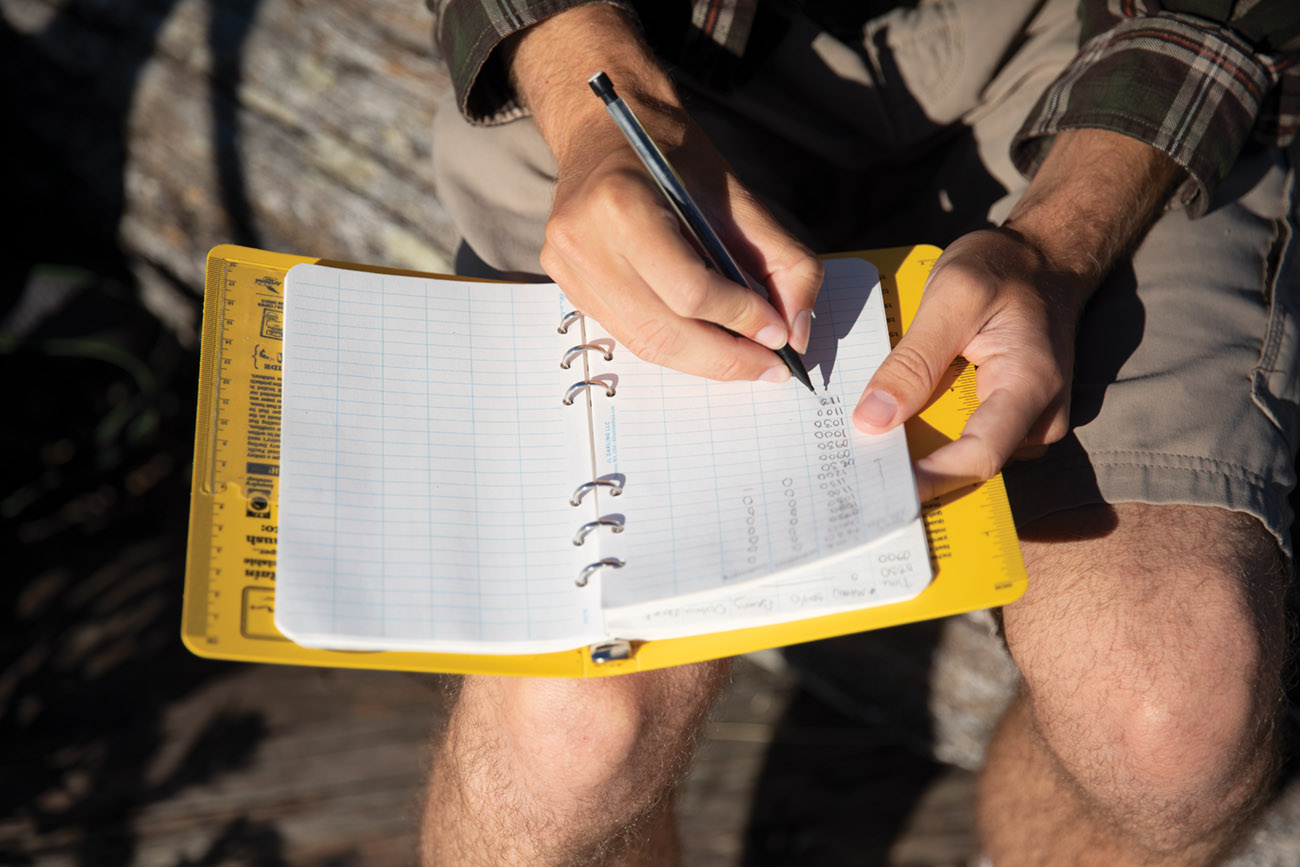

On a Thursday evening, beneath the fluorescent lights of a classroom in Gig Harbor, Wash., Rebekah Lyons pores over an essay she’s writing for a sociology class on gender oppression. She’s chosen to write about the Brett Kavanaugh hearing, and she reads her work aloud, noting a spot that needs a better transition.

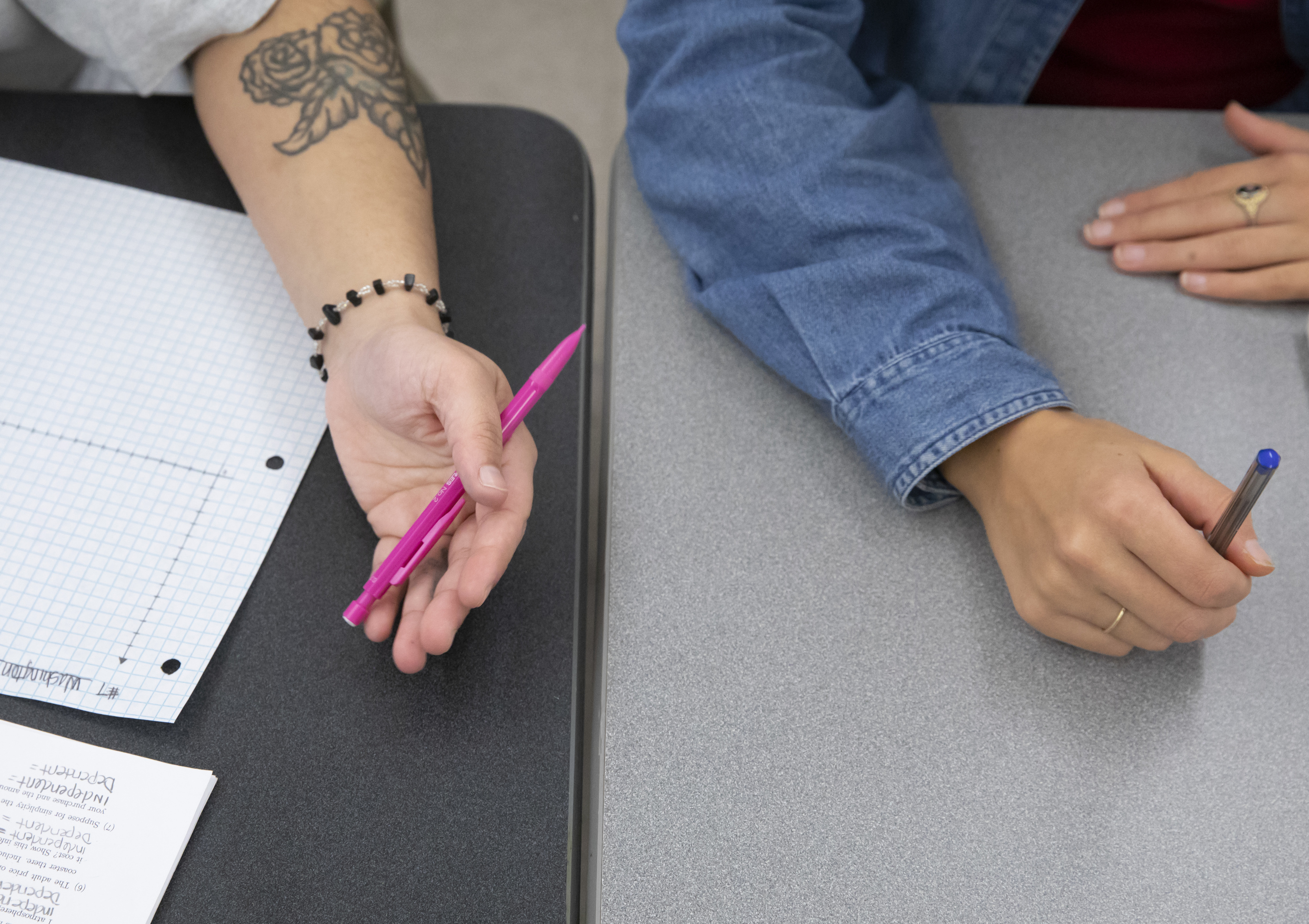

It’s a typical classroom scene, where other students sit in rows of desks chattering about scatter plots and independent variables, and bulletin boards display past projects. But outside, there is a chain-link fence topped with curls of barbed wire, glittering in the lights of the parking lot. Rebekah is an inmate in the Washington Corrections Center for Women, the largest women’s prison in the state, and she is at a study hall for Freedom Education Project Puget Sound (FEPPS), a program that provides college classes for incarcerated women and transgender and nonbinary people housed there.

She recently spent seven months in “the hole”—solitary confinement. “What I had waiting for me when I got out was FEPPS,” she says. “It’s what keeps me from making stupid decisions. It makes me feel like I’m doing something that’s going to count outside.” Rebekah is now a student leader and a member of the FEPPS advisory council. When she’s released, she hopes to become a social worker so that she can help prevent at-risk youths from getting involved in drug use and criminal activity.