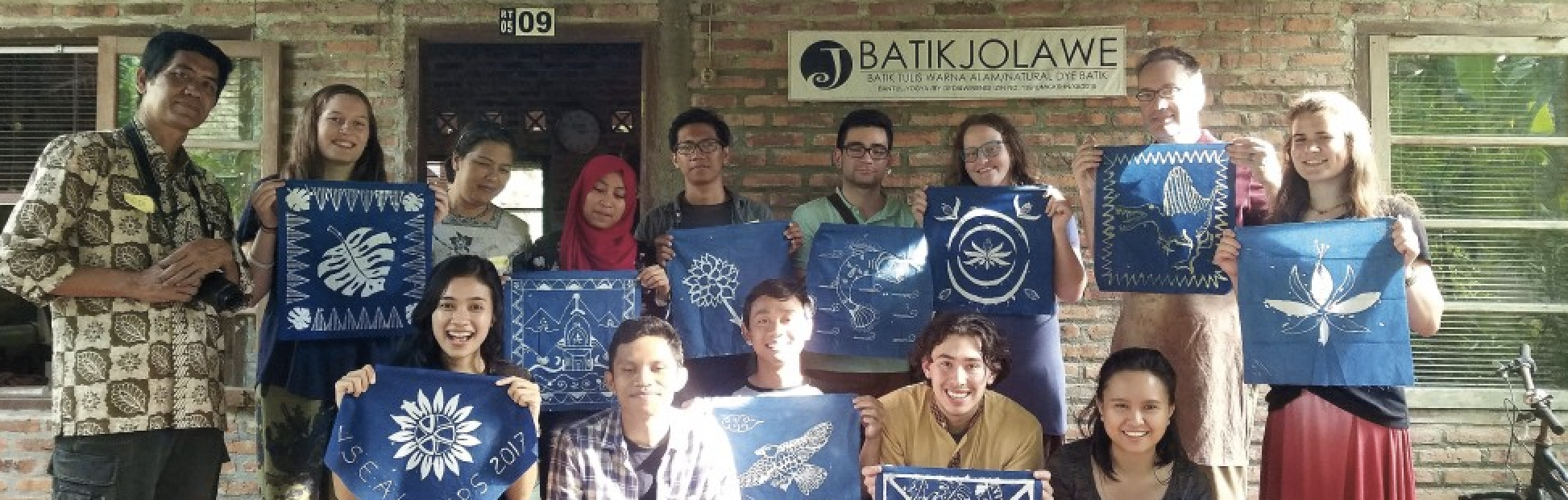

Students and their professors discover modern Argentina

One evening last June, philosophy professor Ariela Tubert and Hispanic studies associate professor Brendan Lanctot led their class along the narrow, labyrinthian paths of Recoleta Cemetery on the acropolis of Buenos Aires, where more than 6,400 above-ground burial sites quietly tell the story of this complicated country.

The 14 students, who had flown in that morning from SeaTac, trailed past statues and mausoleums dating from the 1800s. “We’d been wandering for half an hour when we came to President Alfonsín, and our students got really excited,” says Brendan, recalling the moment he realized this was going to be a special trip. “If you go on a guided tour, they’re going to point out some tomb architecture and where Eva Perón is. But our students knew the history, and from day one they were connecting.”

Their teachers had a personal connection with Buenos Aires: Ariela grew up in the city, and Brendan lived there in his 20s. The semesterlong class, Argentina: Modernity and Its Discontents, was the result of a year and a half of conversations between the two professors. It was designed to cover Argentina’s history—from its fight for independence to its violent transition to a modern nation-state in the 19th century through economic growth and radical political changes in the 20th—as well as contemporary cultural aspects including film, tango, politics, and soccer.