By the time the plane touched down in Jakarta, Indonesia, Lizz Marks ’18 had lost all conception of time. Perhaps, she thought, that was for the best.

Lizz and several other students from the University of Puget Sound had left Seattle at 2 a.m., and arrived two days later. “There was just this moment of elation, of everything materializing and becoming real that we were actually there, but also feeling very unreal,” she says.

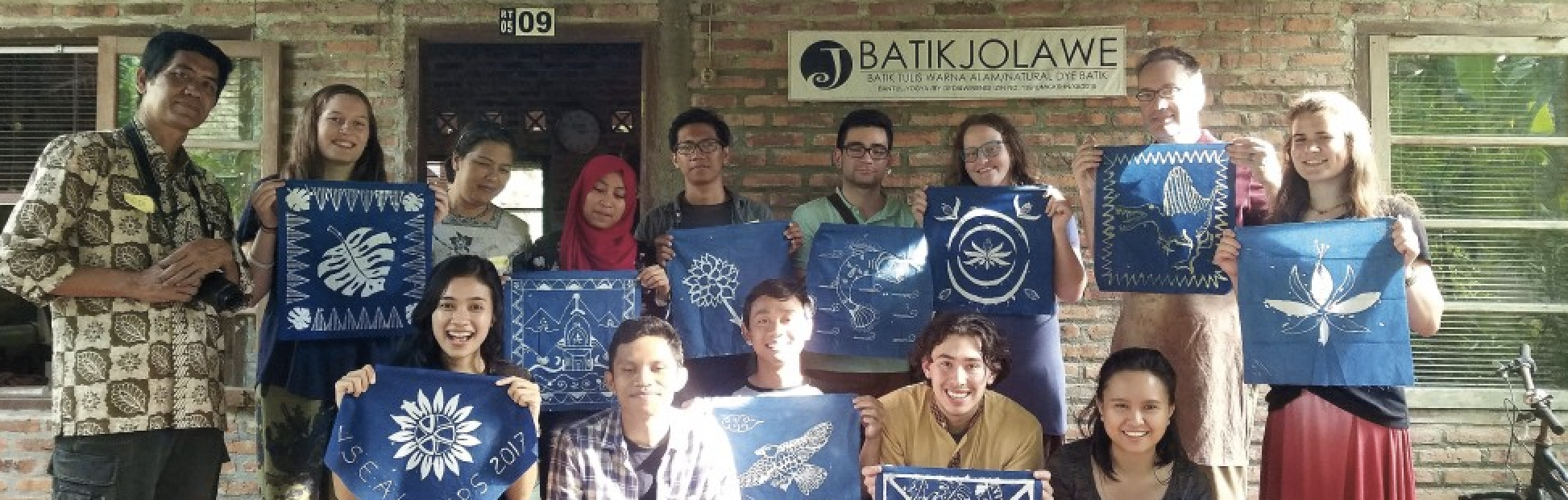

The travelers were students in Professor Gareth Barkin’s Southeast Asia field school course. They tumbled out of the airport into a cab, and careened through the huge, sprawling capital of Indonesia. “I had never been in a nation where the traffic is like that,” Lizz says. “There are three lanes on the freeway, but at least four lanes of cars plus motorbikes zipping around through everything.”

The effect of the time change and the continuous motion was like having each student close their eyes and spinning them around three times. When they opened their eyes, they were standing at the threshold of their rooms, greeting the Indonesian roommates who would live beside them for three weeks. They had been anticipating this moment all semester, and yet had no idea what to expect. “It was very surreal at first, realizing that we were there, and everything was just beginning,” Lizz says.