When one raised hand doesn’t do the trick, try the other one. This was Matthew’s strategy, as the fourth-grader tried desperately to be picked to answer the question, “What is cool about birds?”

The visitor at Jennie Reed Elementary School in Tacoma turned to someone else and moved on. Then another chance came. “If there are 175 birds in this area year-round, and there are an additional 75 migrating ones, how many birds can you guys see total?”

Matthew caught her eye. “Two hundred and fifty,” he murmured, suddenly shy.

“Here’s someone who knows his math. Very good,” she praised. It was a good day for the young scientist.

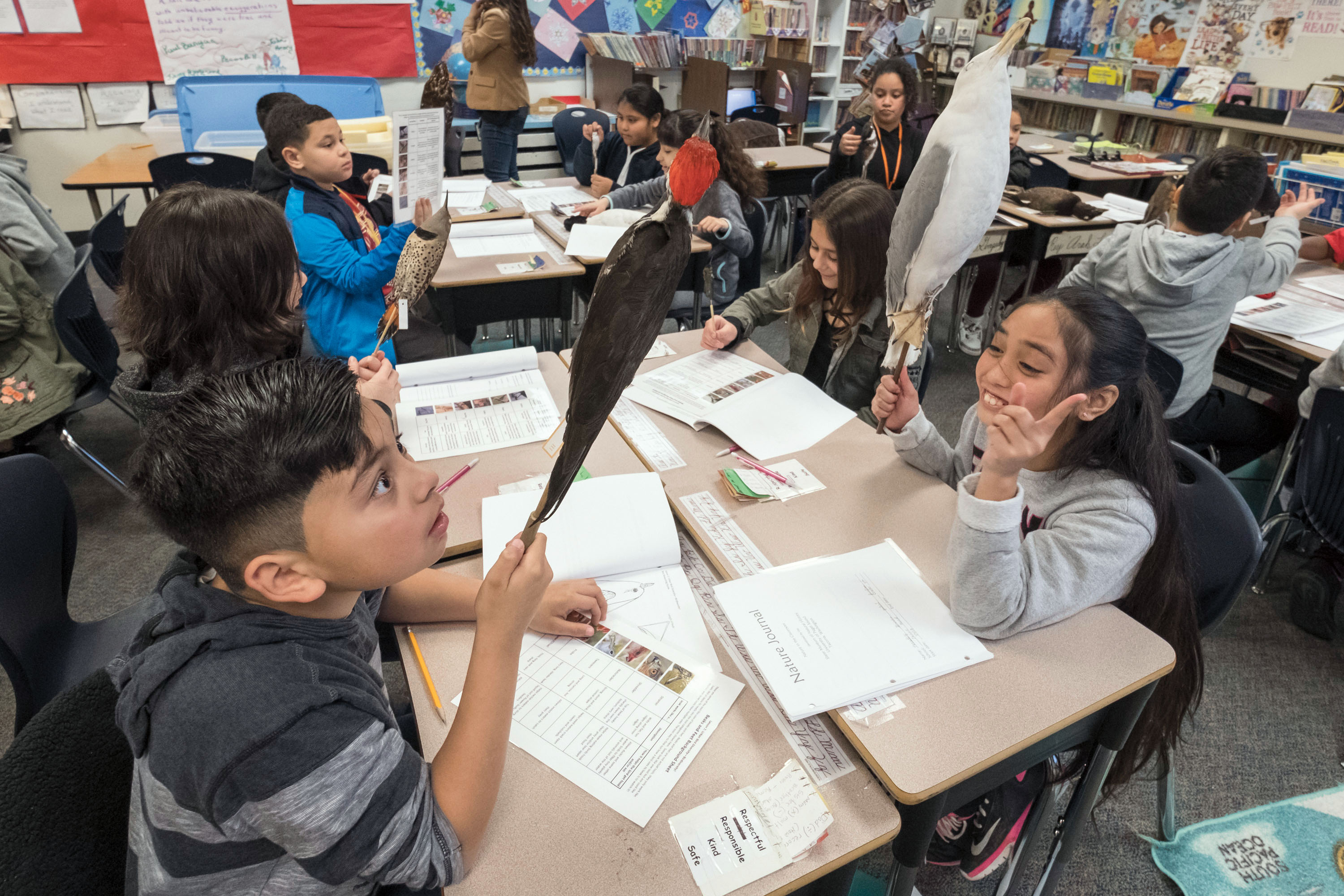

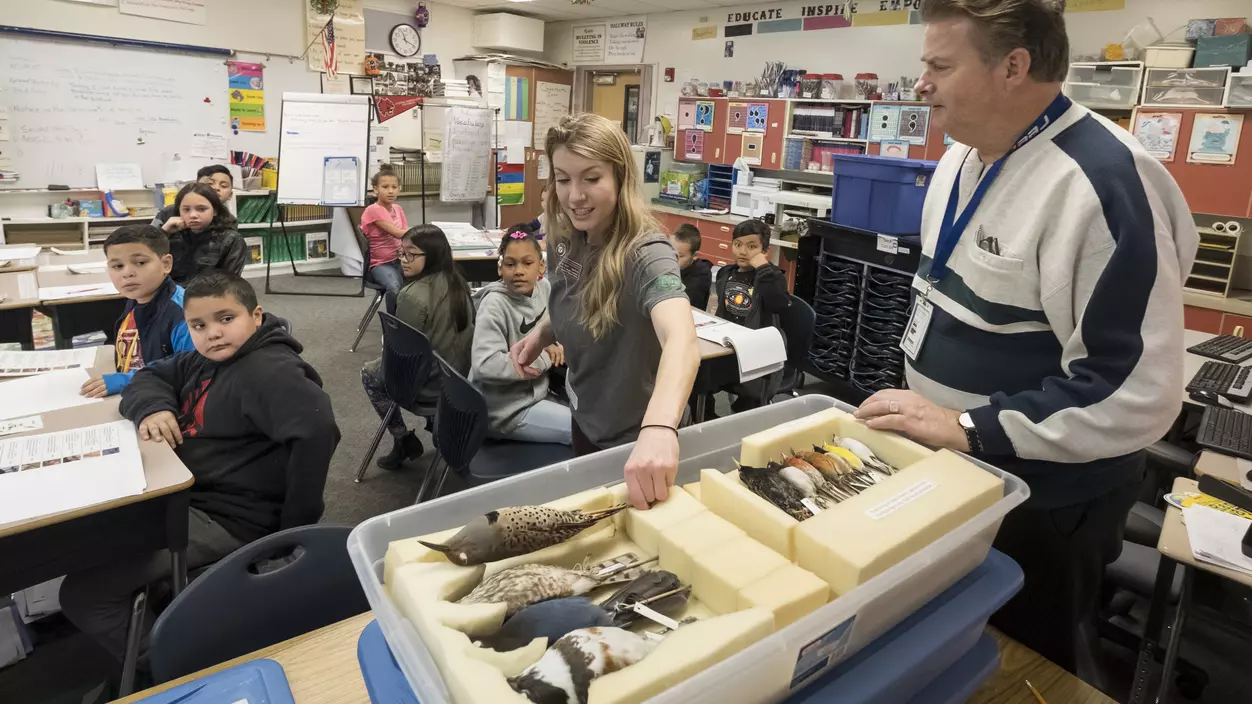

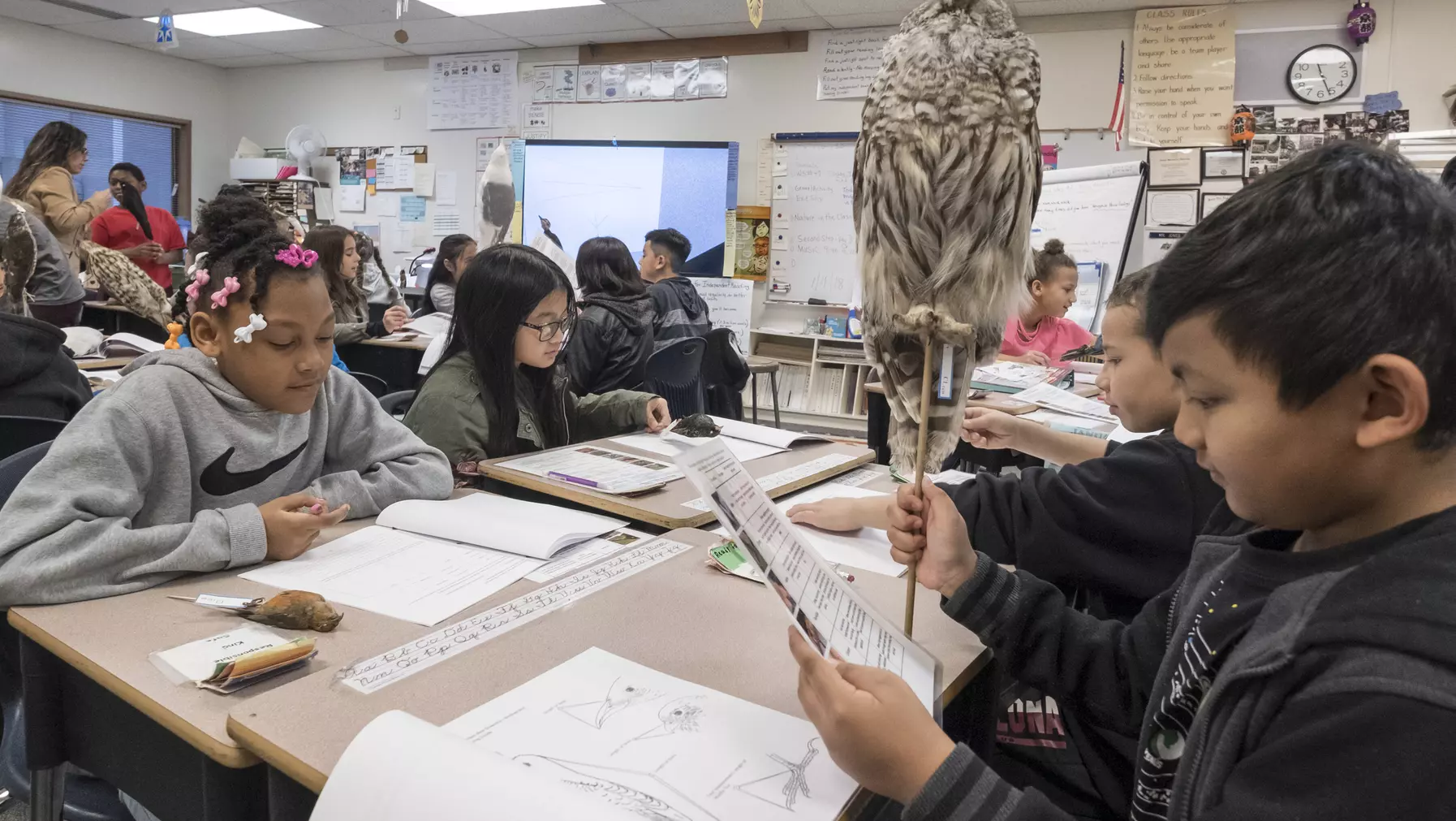

Matthew and the other students were taking part in Nature in the Classroom, an initiative of Puget Sound’s Museum of Natural History. Though this lesson was about birds, the program puts a variety of animal specimens in kids’ hands.