Meet Puget Sound's 14th President by Chuck Luce, Arches, Autumn 2016

His mother’s idea of a bedtime story was reading him the dictionary. In elementary school, he got a perfect attendance certificate nearly every year. In high school, he was the kid you went to for help with your homework. He’s got the unpretentious, dependable, affable traits and quick smile attributed to Midwesterners. Still, he is also an unapologetic workaholic, putting in desk time at home before and after office hours. He likes Halloween, Game of Thrones and Suits, and Tex-Mex, but he doesn’t like surprises. He’s more of a city person than a country person. Please do not bring up the sport of tennis in his presence. Unless that is, you want to hear how Serena Williams did at the U.S. Open or about the lesson he once got from Mary Jo Fernandez. At the faculty awards dinner this past August, he jumped up with his phone and snapped a pic of every winner. And this we note with admiration because it is a trait evolved in all of us Loggers, and yet he’s been among us for only a few months now: He is not one to use the personal pronoun “I” a lot. When talking about the work of the college, he almost always says “we.”

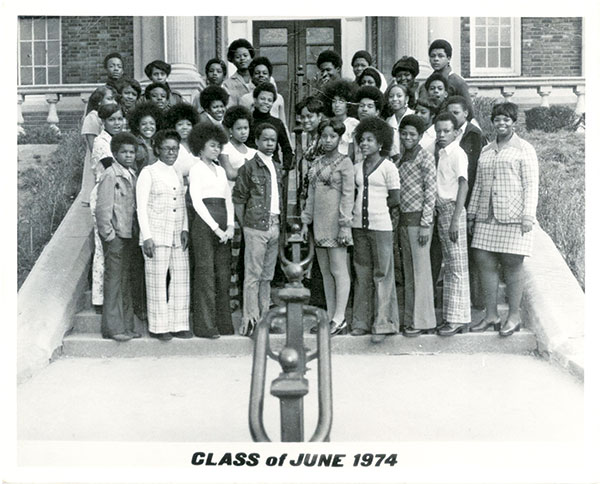

Isiaah Crawford was born in 1960 at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Bethesda, Md. His parents were in the Air Force: his father, a staff sergeant mechanic; his mother, an airman third class teletypist. During the first year of Crawford’s life, his mom, Arthurine, decided that the frequent repostings common for military families were no way to bring up her boy. So she returned to her family, who at that point had moved from McGehee, Ark., to St. Louis.

Ah, St. Louis: The gateway. The departure point for dreamers. Toasted ravioli and gooey butter cake. Anheuser-Busch and McDonnell Douglas. Chuck Berry and Tina Turner. The confluence of two great rivers, Missouri and the ancient unconfinable Mississippi, which has not yet met an obstruction, cannot dance over and laugh at.

St. Louis in the 1960s was a starkly segregated city. Crawford’s family was one of a few African-American families living near what is now known as the Central West End, and also one of only a few families there who were not Catholic.

“All of life revolved around St. Roch’s Parish,” he says. But unlike nearly every other kid he knew, Crawford didn’t go to the neighborhood parochial school. “My mom felt it would be better for me to go to the public school. She thought I needed to be engaged with life beyond our neighborhood and also engage with other African Americans and people of color.”

His dad continued in the military, but his parents went their separate ways; Crawford has no siblings.

From the beginning, it was expressed—ceaselessly—by Crawford’s mother, grandmother, and aunt, who together raised him, that he would be the first in his family to get a college degree.

Crawford says his mother was smart, capable, and fearless; she did not take “no” for an answer. She was a fanatic joiner of community organizations and civic societies. She enjoyed reading (mostly nonfiction) and music of all types. And, he says, above all, she laughed heartily and often.

“She certainly taught me that it was important to work hard and to apply myself fully at all times, but she also thought it was important not to take yourself too seriously, which is a credo I have tried to follow.

“We struggled in a variety of ways,” Crawford says. “My mom, aunt, and grandmother worked very, very hard to provide and to make it possible for me to take advantage of the opportunities available at that time. There were expectations, though. I was expected to contribute to the world. Go and have your fun, they would say, but don’t get into trouble. Don’t mess up. That’s just how it was. I was to focus on my schoolwork.”

Not that hitting the books was always his first focus. “I played every kind of sport you can imagine,” Crawford says. He played basketball and football in the neighborhood and baseball for Soldan High School. He played tennis at the public courts and took lessons there. He played tennis in high school, too, but says he was better at baseball than tennis.

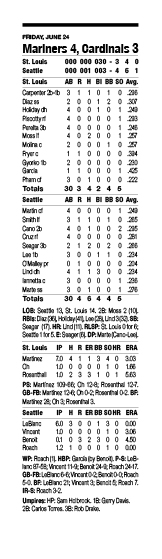

And of course, with Busch Memorial Stadium just down Delmar Boulevard, he was a huge baseball fan, a savant of the game. The kind of guy who could tell you the slugging percentages of not only his hero Cardinals but of every other baseball star at the time. The kind of guy who knew a pitcher should never ignore Lou Brock’s first-base lead. The kind of guy who could tell when Bob Gibson was going to throw his famous high fastball. The kind of guy who could look at a box score (like the one at right) and recite an inning-by-inning narrative of how the game went.

With the adults in his household, though, recreational time was a little different. Crawford and his mom both liked museums, movies, and music. (His first big concert: Tom Jones at the venerable Kiel Auditorium. “The lights, the screaming fans, the music—made quite an impression on a 10-year-old!”) But mostly, he says, “We spent a lot of time in church.” He was an usher on Sundays and in Baptist Training Union, a boot camp for church evangelists.

“I have a singing voice that’s best heard alone in the car so that at least kept me out of the choir.”

When it came time to start thinking about college, Crawford says he was pretty much on his own.

“My family didn’t have a history of doing that sort of thing.”

He chose St. Louis University because it was close to home and its good academic reputation and financial aid offer.

“Also,” he says, “Maybe because of the constant Catholic presence in the neighborhood, the opportunity to go to a Jesuit university appealed to me.”

He entered determined to become a psychology major, an ambition that came about because of an old movie. Awake in the wee hours one night watching TV when he was in 10th grade, he happened upon the 1957 film The Three Faces of Eve, about the real-life Chris Costner Sizemore, who suffered from a dissociative identity disorder.

“I was absolutely fascinated, he recalls. “The next morning, I got to school early so I could be the first person in the library. I wanted to look up multiple personality disorders. What was abnormal psychology? What was psychotherapy? I think I missed my first class because I was so enthralled with what I was reading. From that moment on, I wanted to be a psychologist.”

He received reinforcement for that resolve when the Rev. Dr. Benjamin Hooks, then executive director and CEO of the NAACP, came to speak at St. Louis U.

“I don’t recall exactly how it came to pass, but I was tasked with going to the airport to pick him up. That I remember like it was yesterday. Rev. Hooks was inquisitive—about me and my goals and what I planned to do with my education. I hesitantly shared with him that I was thinking about going to graduate school to become a psychologist, and I’m sure the doubt in my voice was evident. I remember him asking me very nicely to pull the car over. When I did, he turned and looked directly into my eyes and said, 'Of course you can do it! We do not have time for you to have doubts about yourself. Get about it!'"

Crawford says he also enjoyed his college classes in theology and philosophy.

“For a while there, I actually thought about double-majoring in philosophy and psychology. Or maybe majoring in philosophy and minoring in psychology. I remember telling my mom that on the phone and … dead silence. You could hear crickets in the backyard. To her, I was going to be a medical doctor or a lawyer,” he says. “But when I told her I could get a Ph.D., that I could be a doctor of psychology, she responded, ‘OK, Baby. You can do that if you want to.’”

Crawford lived on campus his first three years at SLU. During his senior year, his grandmother developed Alzheimer’s, so he moved home to help his mother and aunt care for her. Grandma Velma passed away in December of his senior year. There was deeper heartbreak ahead. Later that spring, his mother, the woman who had worked her whole life to get her son the college education that circumstances did not allow her to complete, died of a heart attack while at her office a week before graduation.

“She had gone out and bought a commencement outfit. She never got to use it. We buried her in that dress, and we buried my diploma with her.”

A career in colleges

“I had been admitted to DePaul University’s Ph.D. program in Chicago. That’s what my mom would have wanted me to do. Plus, the idea of living independently and taking advantage of all that a bigger city had to offer really appealed to me.” Crawford says he went to graduate school thinking he’d eventually be a therapist working at a psychiatric hospital, a community mental health center, or a counseling center at a university. “Never for a moment did I think I’d be an academic,” he says. “So I’m finishing up my dissertation [back when HIV/AIDs was not yet well understood, it was on developing an awareness and prevention program for school students], and one of my primary professors, Leonard Jason, who was a very encouraging and supportive advisor, calls me up on the phone and says, ‘Isiaah, Loyola University Chicago has an opening for an assistant professor. I think you should apply.’

“I said, ‘Well, Professor Jason, thank you for bringing it to my attention, but I don’t think I want to do that.’ I was much more focused on the clinical side.

“Jason said, ‘Yeah, I know. But I would really like for you to apply for the job.

“‘Dr. Jason, I don’t think that’s going to be right for me.’

“To which he responded, ‘Isiaah! Apply for the damn job!’

“I didn’t have full-time work lined up, so I thought, OK, well, if I get the teaching position, I could do that while I study for the licensing exam and then move on.

“Thirty years later, here I am.”

At Loyola, Crawford was able to get his professional certification and set up a practice specializing in addictive behaviors and depression (he is still a licensed psychologist) while also continuing research on human sexuality, health promotion, and psychotherapeutic process. (See sidebar below.)

It turned out Crawford loved working with students. His Ph.D. advisor had seen in him something he had not yet realized himself—that he would find the demands of being a good teacher and staying informed and current in his field would satisfy his intellectual curiosity, and that he also could satisfy his sensibility to assist others in achieving their goals, as he himself had been assisted.

“That’s been the story of my life,” he says. “I’ve been very fortunate that the universe had brought me in contact with people who wanted to be helpful, who offered encouragement and support when it was necessary. And those examples served me later when I was the one in a position to be a mentor.”

“Even as a graduate student in the 1980s, he was ahead of his time, working on AIDS prevention and minority issues,” his former professor, Leonard Jason, says. “I always knew that his independence, creativity, and a good sense of humor would propel him to positions of leadership where he would be able to help others gain academic credentials for success.”

It was this capacity for empathy that got him started in university administration. He had observed that his colleague at the time, Patricia Rupert, who directed Loyola’s clinical psychology training program, was swamped, and so he offered to be her volunteer assistant.

“I was able to take some burden off her so she could do other, higher-level things,” Crawford recalls. “It also allowed me to work more directly with our graduate students and prospective students. Still, to this day, if I can identify some way, somehow that I can be helpful to someone—to help them overcome an obstacle that was in their way or solve a problem that was before them or remove a frustration so that they can continue to pursue their aspirations, that is very satisfying to me. That’s a good day. I really do perceive myself as being a service-oriented leader. I’m a psychologist, you know, so that kind of runs consistent with that.”

Loyola clearly knew administrative talent when it presented itself. Crawford was a natural successor for leading the clinical psych program. He then became chair of the department of psychology and, later, dean of arts and sciences.

In 2008 he was recruited to be Seattle University’s provost. In that role, he directed the Division of Academic Affairs. He oversaw the university’s schools and colleges, libraries, enrollment, information technology, institutional research, and offices supporting academic achievement, faculty affairs, and global engagement.

It was a big move in some ways, with vastly different cultural, geographical, and meteorological attributes to get used to. (“I learned that there really are 50 shades of gray out here in the Pacific Northwest,” he says.)

Stephen Sundborg, president of Seattle University, says indeed Crawford needed a little time to adjust to life in the Northwest.

“He had always been a city kid,” says Sundborg. “The whole outdoors thing was new to him. His first year here, we met the administrators’ cabinet in Sun Valley, Idaho. Nine of us. One day we took a break and went fly fishing. There was Isiaah, out there in waders fishing on the Big Wood River, laughing so hard he could barely breathe but gamely giving it a go.”

In other ways, though, Isiaah found himself in a familiar academic environment: a school that encourages in its students the rigorous application of intellectual curiosity and the principles of social justice, run by Catholic priests.

“Isiaah has extraordinarily high academic expectations,” says Sundborg. “He will seek that in every decision he makes. He elevated the role of scholarship at Seattle University. He set up a center for faculty scholarship, got national grants for a scholarship, planned days to recognize scholarship, set up monetary scholarship awards. And he also naturally brought a strong influence on inclusive excellence and diversity because of who he is and how he connects with people.”

“At Seattle U, I didn’t have the opportunity to work as directly with students as I had as dean,” Crawford says, “but I tried to do as much as I could to stay in contact with them. For example, I had regular meetings with 10 to 12 students—just regular students, not student government officers or superstar students. I’d buy them lunch, and we would sit and just talk. Also, President Sundborg, Executive VP Tim Leary, and I would meet with faculty and a group of staff for breakfast—different people each time— four times a year. We didn’t really talk about university business; we just got to know people. I really enjoyed that. These are practices I hope to continue here.”

The process of getting him “here,” of finding a new president, was long, complex, interesting, and not without its surprises. It took a year. A 14-member committee comprising Puget Sound trustees and faculty, student, staff, and alumni representatives started by identifying leadership priorities and personal qualities that they thought would be a good fit for the college. After the call went out, the applicant pool included sitting presidents and other leaders at some truly outstanding colleges in more than 30 states, plus three international universities. These were winnowed down to 10 semifinalists.

In introducing him to the campus, then-chair of the board of trustees Rick Brooks ’82 said: “Crawford impressed the search committee with his candor, collaborative nature, commitment to community, and passionate belief in the ideals of a liberal arts education. He rose throughout the process to become the clear choice—best suited to this institution at this place and time, and best equipped to leverage the opportunities and meet the challenges that face us now and in the future. As a college that derives so much of its identity from the culture, values, and opportunities of the Pacific Northwest, we were especially pleased to have found Puget Sound’s next president so close to home.”

“I wouldn’t say that becoming a college president was an ambition,” Crawford says. “It certainly crossed my mind, and it seemed to cross the minds of other people I worked around. I got to the point where I thought I could be helpful to the right institution if we could find each other. But it wasn’t a linear path in my thinking.”

And it’s not exactly a job that someone just cruises into. Especially these days. As America drifts ever more from public support of higher education, access and affordability are huge challenges. So are shifting demographics, accountability, keeping up with technology, meeting the expectations of Title IX—we could go on. But the task is noble, and Crawford says he believes wholeheartedly in the transformative power of a liberal arts education.

“This is a year I want to be out of the office—a lot. So I can learn about the history and people of Puget Sound, and so people can learn about me. I hope to continue the trajectory that President Thomas and previous presidents have set the college on to elevate its national profile and carry forward its commitment to foster an inclusive campus community. My own identities as an individual and the intersectionalities differ from my predecessors in this role. But my charge—to support the institution in achieving new levels of excellence—remains the same. Diversity is an important part of that charge and an essential component of a truly liberating liberal arts college experience.”

Out of the office

“I’m an aging weekend warrior sort of guy. At this mature age, I’m still out there playing in a softball league, running around pretending I am in my mid-30s.”

Our mountains and rivers and forests have little by little drawn him to them. He says he has taken up snowshoeing and is looking forward to the winter season. He also remains interested in tennis. “I’m in love with the Williams sisters and have been able to see them play in person.”

He enjoys traveling. “I’ve been to all but three states of the United States—Vermont, West Virginia, and North Dakota, and I have been blessed to travel throughout Europe, China, and South America.”

Among the more stark cultural intersections for him was getting the news that his beloved Cardinals had won the 2006 World Series while he was on the Great Wall of China. I loved visiting Spain. “One of the most impressive structures I’ve seen is La Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. And who doesn’t like Paris?” he says.

“I’ve been known to enjoy a good wine or other adult beverage now and then—shaken, not stirred.” (OK, we get it.)

“I don’t have time to read for pleasure as much as I would like, but when I do, I love murder mysteries; the schlockier, the better.” On his bedside table when I interviewed him: the psychological thriller The Girl on the Train.

Movies remain a favorite pastime, too. “I like that genre of film from the 1930s and 1940s, like Double Indemnity, Maltese Falcon, All About Eve. I can’t wait to see the new Bourne film.

“Restaurant is one of my hobbies with Kent.”

That would be his spouse and partner of 15 years, Kent Korneisel. The two were married in June. Kent was born in Britt, Iowa. Population about 2,100. He got his undergraduate degree at Iowa State and then went to Illinois College of Optometry, where he earned a doctoral degree in optometry. He is working in an optometry practice at Costco in Tukwila. Kent is an avid chef and gardener.

“And I have forced him to become a sports fan,” Crawford says. “Primarily of tennis, but we also watch baseball and football together.”

They have rented their house in West Seattle and have made the president’s house on campus their primary residence.

Observations

For the past several months, this correspondent has been listening to our new president every chance he gets: at formal gatherings and going about the quotidian campus grind and for several hours in private interviews. On freshmen move-in day, he was everywhere, with that smile you wish you had, introducing himself and making conversation like a neighbor. At the annual start-of-the-school- year meeting with faculty and staff, during which he lightened up the usual stats about the new freshman class and other administrative details with feelings about the beginning of this, his own freshman year in Tacoma.

Here is a man, I think, who genuinely gets great satisfaction from being a facilitator—from making it possible whenever he can to help people achieve what they are trying to achieve. I have observed in him a dedication to the work, an insistence on effort, an insistence on nothing less than perfection, but these things are overlain with humility and good humor. And we ( I emphasize “we” because, as I noted at the top of this introduction, that is how he thinks), we are looking forward to getting about it and together continuing the succession of good—making it possible for another generation of Puget Sound graduates to get out there and do what they do—for the benefit of us all.

Chuck Luce has been the editor of this magazine since 1998. You can hear President Crawford talking about his move from Chicago to Seattle, thoughts on the role of a college president these days, first impressions of Puget Sound, and other topics at the college’s just-launched podcast site: pugetsound.edu/whatwedo.